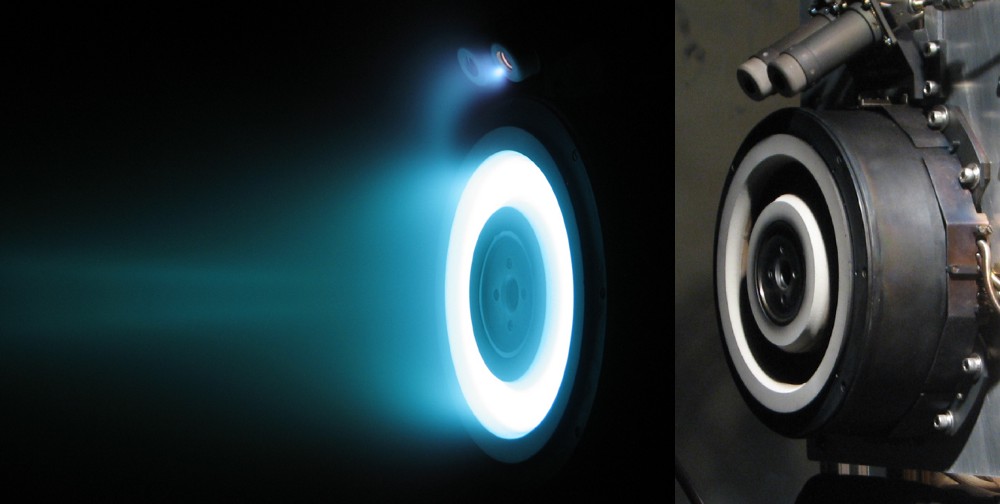

Introduction to Electric Propulsion

What would you think if you were told that today’s space travel relies on non-combustible fuel? You may be tempted to think this is science fiction, however this is exactly how the Hall Effect Thruster functions. Once a spacecraft is in space, this invention applies about the same amount of force that you would feel holding a stack of 10 quarters or a single tennis ball. (10 16 18) Over time in the frictionless void of space, the spacecraft is slowly and continuously accelerated to extreme velocities, up to 200,000 mph. (18) Typically a noble gas (like xenon) is used as a fuel in a process that is over twice as efficient as chemical thrusters. (18) Welcome to the world of electric propulsion.

Introduction to the Hall Effect Thruster

The Hall Effect Thruster is a type of electric propulsion, meaning it uses electric and magnetic fields to accelerate gaseous Xenon propellant to incredible speeds creating thrust for the spacecraft. This differs from traditional chemical thrusters which burn propellant to create thrust for the spacecraft.

Xenon Propellant

The choice to use a noble gas like xenon as propellant is three-fold. First, Xenon is a large, heavy atom which produces high thrust. Second, it is easily ionized. Lastly noble gasses are inert meaning that they are safe to use with a wide variety of other spacecraft materials. (12 18)

-

Improved efficiency:

Electric propulsion systems (like Hall Effect Thrusters) have high specific impulse allowing for them to use significantly less propellant on a mission than with chemical thrusters. (12) For example, the Dawn spacecraft held only 937 lbs of Xenon propellant. (23) The space shuttle's orbiter holds roughly 11,000 lbs of liquid MMH fuel alone and a single space shuttle rocket booster has a solid propellant weight of 1,000,000 lbs. (20 24) -

Increased lifetime:

The Hall Effect thrusters used on the NASA PSYCHE mission have lifetimes of around 5,000 hours. To compare, space shuttle rocket boosters which use solid chemical propellant have operational times of only 2 minutes. (20)